Building IoT devices: scaling from 10 - 1,000 devices

This post was originally published on Mbed Developer Blog.

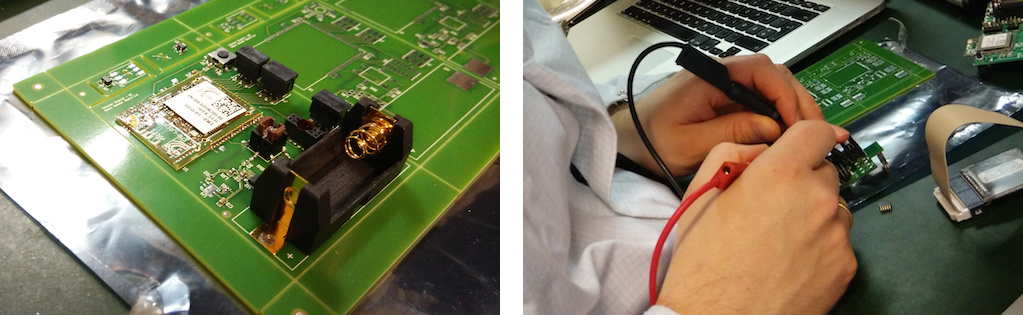

Unbeknownst to many of you, December 10th, 2015 was a historic day. That morning, I walked into the building of Noca - a factory in Trondheim, Norway - wearing a white lab coat, a JTAG in my hand, and with a LoRaWAN base station in my backpack. That day, we could finally inspect the very first factory samples of the LoRa device that my team and I had been developing. The moment you see your components mounted on a PCB is both the most exciting and most scary moment in the life of any developer working on a hardware project.

On the left: First factory sample of our mounted PCB. On the right: Trying to figure out why our JTAG header did not work properly.

There’s excitement because your design has suddenly become real, and fear because any mistake that you missed might as well send you back to the drawing board. This, however, is what hardware design is all about. This is the pinnacle of months of planning, drawing schematics, writing software, and haggling about budget.

Unfortunately, many hardware projects never make it this far. Although the prototyping of hardware has never been easier, actually producing that same hardware seems like a big mountain to climb. On the prototyping side, we have seen a huge advent in hobbyist-friendly developer boards, great SDKs, and an enormous amount of cheap sensors - enabled by the smartphone revolution, which has pushed prices for advanced technology (like accelerometers) down to pennies on the dollar. Sadly, that’s often where projects stop. A good prototype might be replicated a few more times on a development board with a breadboard, soldered together and given away to some friends and colleagues, but that’s not a scalable model.

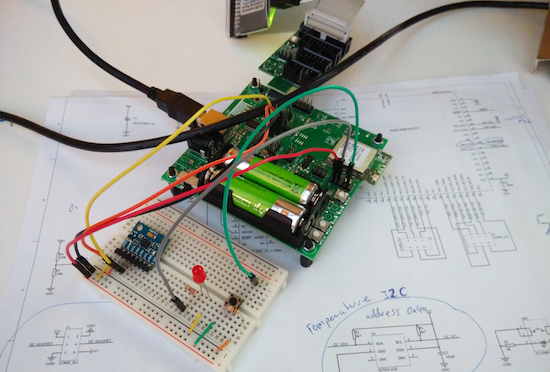

While prototyping. Underneath the breadboard are the schematics for the final board.

Despite all this, bringing a prototype into production is probably the holy grail for the Internet of Things. If any ordinary developer - without proper training as a hardware engineer or even as an embedded software engineer - can design devices that will hit the marketplace, this creates a huge opportunity for companies. Your in-house developers have the best knowledge of your field of business and they have intimate knowledge of any challenges that can be solved with IoT. If they can quickly develop custom hardware for a use-case that specifically benefits your company, that might provide you with a competitive edge. The team here at ARM mbed want to play a pivotal role in creating that opportunity. Are we there yet? No. Are we going in the right direction? I think so.

Developing production-quality software for embedded devices is getting easier and easier. In the past, you would take an RTOS and then build your application from scratch. You were 100% in charge of security, power consumption and efficient radio drivers. That’s no longer the case. The whole industry is moving into a model where you can run a larger, well-tested stack of middleware on your device, then build your application on top of this middleware. Suddenly, you can take advantage of clever schedulers which will handle power management for you, re-use well-tested libraries (since they’re written against a hardware abstraction layer rather than straight against the device hardware) and build on top of radio-agnostic network drivers. mbed OS 5 provides a great software foundation which can do exactly that.

On the hardware side, things are more difficult. Building great hardware requires a number of things that are less generic. First, turning your design from a breadboard to a PCB. A big advantage that we have on mbed is that the MCUs that development boards use are modern 32-bits ARM CPUs that are readily available on sites like DigiKey. As a result, you can design your own board around the same MCU and run your mbed program directly on your new board. We also support a number of modules which combine an MCU and a radio (like the Nordic Semiconductors nRF52832 or the Multitech mDot) so you don’t have to do your own RF work.

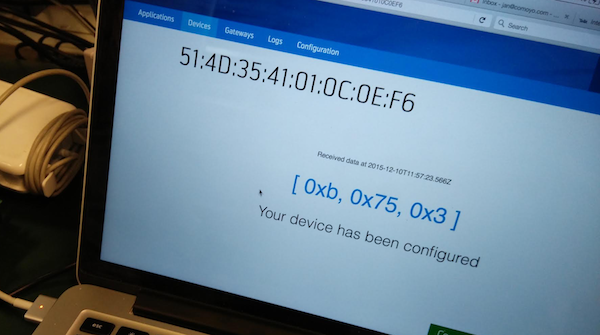

When our first device started working and sending data over the network. We used a module with a Cortex-M0+ and a SX1272 LoRa radio to go to market faster.

We also help by open-sourcing our debugging hardware. Every mbed Enabled development board uses DAPLink (or STLink) to mount as a mass-storage device and to enable a debug interface. By using our SWDAP debugging probe you can use exactly the same flashing and debugging methods on your own board as on your development board, without requiring a bulky connector or USB port on your board.

On top of that, we have a number of reference designs, including our wearable reference design and our 6LoWPAN border router hat, which can be used freely and contains schematics, hardware designs and all the necessary software. All built on top of our open source mbed Hardware Development Kit.

Having these resources doesn’t trivialize the entire process, but we think that we’re making progress. We have plenty of experience building hardware - including the hardware for the BBC micro:bit - and we will be leveraging that experience to make mbed the ideal development platform. We want to empower developers to build IoT solutions that can scale from 10 to 1,000 devices, letting you make a real mark in the IoT space.

If you want to kickstart your new IoT project or learn more about designing hardware, visit mbed Connect (http://mbed.com/mbedconnect16), our first mbed developer conference on the 24th of October in Santa Clara, CA! We’ll have sessions about hardware design by Chris Styles, who designed the schematics for the BBC micro:bit and many other mbed boards, and by Jan Jongboom and Mac Lobdell on building production-ready firmware. Sign up now for just $25!

-

Jan Jongboom is Developer Evangelist IoT at ARM and loves to turn ideas into products.