Why JavaScript on microcontrollers makes sense

This post was originally published on Mbed Developer Blog.

Three weeks ago, during JSConf.asia 2016, we announced JavaScript on mbed, which enables developers to write firmware for IoT devices in JavaScript. This is not done by transpiling JavaScript into C++ or Assembly, but rather by running the JerryScript VM directly on top of ARM’s mbed OS 5, which can be run on cost-effective microcontrollers. This announcement caused an interesting debate, including a heated thread on the Reddit Programming subreddit with 192 comments.

And yes, there are valid concerns. JavaScript will be more resource hungry than native code, and it might not be the best idea for every embedded application. But, we also believe that there are some great benefits to running a dynamic, interpreted language on a microcontroller, especially for IoT devices. I’d like to share some of these benefits.

We do want to stress that we’re talking about writing the application layer in a higher level language. The core parts of your embedded OS, including the scheduler, peripheral drivers and network stack will remain native.

Event-driven model

An event-driven model makes a lot of sense for IoT devices, especially on smaller sensor nodes. Many of them only run a networking stack and some peripherals, and respond either to events from the network, some interrupts or the real time clock. Using an event loop for scheduling, rather than manual scheduling, helps with a number of common problems when programming microcontrollers:

- Networking stacks that want to take over the main loop of the program, making it impossible to mix multiple networking stacks. Here’s an example (line 44).

- Delegation from interrupt context back to main thread to do actual work. Semaphores and mailboxes are complex beasts and taint your code very quickly. Also, the problem might not manifest itself straight away; doing things in ISRs is often fine with GCC but crashes when compiling with ARMCC.

With JavaScript on a microcontroller, not only can we enforce event-driven programming - it’s also a model that is already familiar to every JS developer, since that’s how JS in the browser works. The higher level APIs that we need to introduce can even completely hide the synchronous calls, similar to how node.js works for server-side code. A main-function or busy-sleep on the CPU is a concept not known in JavaScript, making it a very friendly language to experiment with event-loop constructs on microcontrollers. Additionally, because all JS code will be event loop aware, we can automatically dispatch events from interrupts, not even giving users the opportunity to do blocking calls in an ISR context.

Of course this model is not new, and we can run event loops in C++ code (we have a library for that as part of core mbed OS), but it’s a model that only works if everyone in the ecosystem plays along. When we tried to enforce the evented model as part of mbed OS 3 we ran into many problems, because it broke compatibility with a lot of libraries that were not written with the event loop in mind. This is the same problem that server-side languages faced before, where early attempts at event-driven development like Python’s Twisted or Ruby’s EventMachine never gained a large following, in part due to incompatibilities with the existing ecosystem. Node.js - without an existing ecosystem of synchronous libraries - however managed to popularize the event-driven programming model.

Battery life

Event loops give us an additional benefit. When we’re aware of all scheduling, our OS is allowed to take over the sleep management schedule on your device. If we need to do sensor readings every 5 minutes, we can schedule this event and put the MCU in deep sleep in between. Combined with drivers implementing wake locks (for a reference of how this could work, see here), and furthering our work on tickless idle mode, we could get good sleep mode out of the box for many scenarios.

Cheaper firmware updates

One of the difficult problems in building IoT devices is encountered while patching devices in the field. For compiled code, it requires enough flash to hold two versions of the firmware as well as a bootloader which knows about firmware updates. The firmware is binary, which means it also generates relatively large diff files, even for small code updates. bsdiff generates 3-4 Kb diff files even for single line changes - while also being memory hungry. This makes firmware updates impossible on constraint networking protocols like LoRaWAN.

When we run an interpreted language, our application logic is just text, separated from the native libraries and the VM. This makes it easy to send new firmware to the device (it’s just text) and it compresses and diffs very well. This comes with the downside that you can only patch your application logic, but it can be combined with full device firmware update like we have in mbed Cloud to do cheap updates when possible, and full updates when necessary.

Developer tools innovations

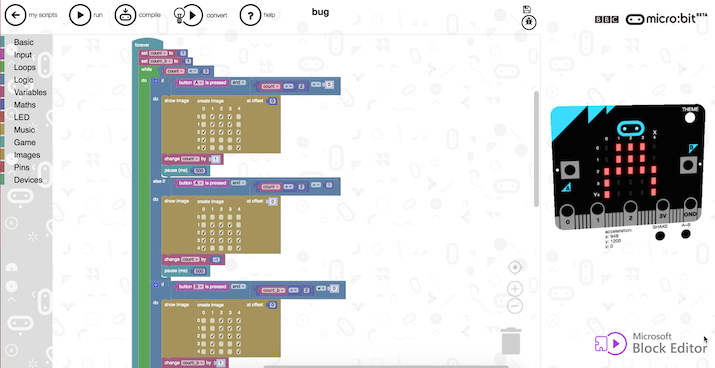

A higher level language also allows us to think of new ways of writing code, by iterating faster on development tools. We have seen this with the BBC micro:bit project - in which a million children in the UK learned how to program as part of their primary school curriculum. The micro:bit comes with a visual block-based programming language in which students can create their program by dragging and dropping blocks together. On top of this the (in-browser) IDE also has a simulator present, which shows a simulated micro:bit running the program that was just created.

The simulator provides a fantastic way of shortening the develop test feedback loop from minutes to seconds. This is all enabled by the abstraction layer that the block editor provides. The same blocks can be compiled down to C++ to run on a device, or interpreted by the browser and be used to visualize the program in the simulator.

BBC:microbit Block Editor, with simulator running on the right side of the screen.

The key is that the abstraction is high enough that the user just sees peripherals. For the micro:bit, we want to have a ‘Screen’ peripheral, rather than simulating the I2C bus. This abstraction layer in a low-level language is much harder to enforce (although not impossible, of course). In addition, if we write application code in JavaScript (rather than MicroPython for example), we can even run the simulator completely in the browser. One of the first things we did for JS on mbed was to develop an in-browser simulator that supported Bluetooth.

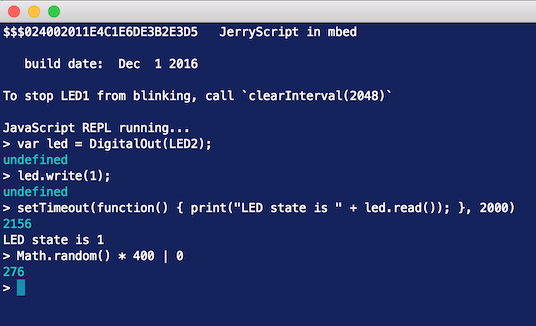

REPL

One of the other models that an interpreted language provides is the ability to run a Read-Eval-Print-Loop (REPL) on a device. With an REPL, we are given a shell in which we can interact with the device dynamically, without having to recompile code or flash new firmware. This allows for very flexible prototyping. Not sure if the datasheet is right for an external peripheral? Just use the REPL to quickly fire some I2C or UART messages to it. Again, this is about shortening the feedback loop and is also very useful if your actual application will be written in C++. Our REPL for JS on mbed is located here.

We might be able to take this further, offering pre-built images containing the core OS and a networking stack. When the device comes online, it can be programmed straight from the online compiler, storing the application code in flash. This could reduce the tools overhead for new developers even more.

Cost might be worth it (in the near future)

At the moment, software development is a relatively small part of the cost when building IoT devices; hardware design is the expensive part - especially because it’s easier to patch software than hardware. Having to spend a dollar extra to add more RAM or flash to your device, because you’re shipping it with a JavaScript VM, will drive up cost faster than the development time savings are worth.

But, times are changing. With the advent of cheap modules, which combine MCUs and radios, the upfront cost of designing connected devices is being driven down by not having to pay an RF engineer or do certification for your device. Although this raises the price per unit, it will become feasible to do smaller runs of devices, creating a market where smaller companies can also produce (relatively) low-cost custom IoT solutions.

If you can save time developing your firmware by using a higher level language (at the price of a beefier MCU), it might be cost-effective at low volumes. With the price of modules constantly dropping (here’s a $2 WiFi module with a Cortex-M3 and 512K RAM), the cost effectiveness threshold will go up over time.

Conclusion

While JavaScript (and other high level languages) on microcontrollers have downsides, they also allow us to try interesting new programming models. For instance, we can create new development tools that shorten the develop-test feedback loop like REPLs or simulators. We can also abstract away common problems that embedded developers have, like dispatching from ISRs to the main thread. In addition, it allows us to experiment with new features, like automatic sleep management.

For the majority of IoT devices, C/C++ will still be the way to go. However, JavaScript on your microcontroller will be a great prototyping tool, or maybe even a proper and cost-effective choice for teams doing smaller runs of hardware.

For more information on JavaScript on mbed, visit mbed.com/js, or watch the introduction of the project at JSConf.asia 2016 here:

-

Jan Jongboom is Developer Evangelist IoT at ARM. He has written about building hardware before.