Streaming data of cows during Data Science Africa

This post was originally published on Mbed Developer Blog.

Last month, Arm sponsored Data Science Africa 2017, a machine learning and data science conference held annually in East Africa. This year, the Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology in Arusha, Tanzania hosted the 300 attendees for five days of workshops, talks and interesting conversations. Arm hosted a two-day IoT workshop and a keynote, but the fun starts when you apply your acquired knowledge to a real-life scenario. Thus, on the Saturday after the conference, Jan Jongboom (Developer Evangelist), Damon Civin (Lead Data Scientist) and 15 conference attendees, headed to the outskirts of Arusha for some good, old-fashioned field work.

The problem

The first visit of the day was to a dairy farm, where Dr. Ciira Maina presented the premise that behavioral analysis of cows can predict whether a cow is in heat, or when a cow is becoming sick. This is valuable information because insemination timing is important, semen samples are expensive, and preventing sickness is better than curing. However, analyzing a cow’s behavior requires data…

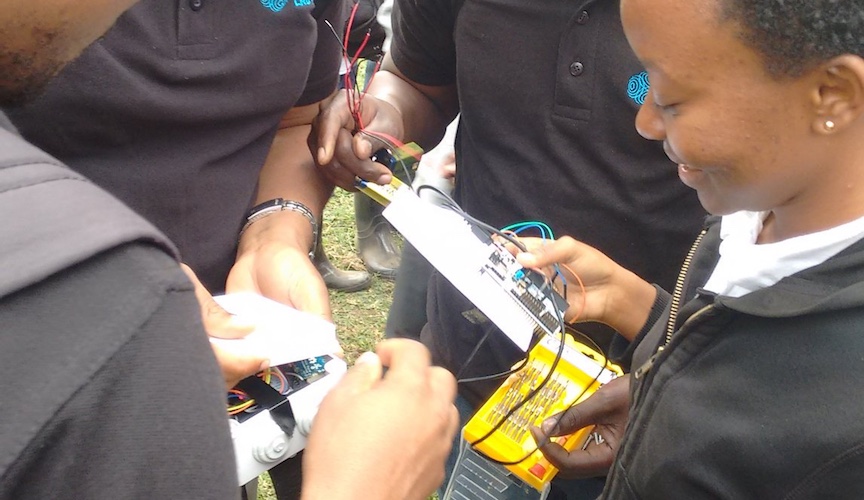

Armed with a plastic case, an Arm Mbed nabled NUCLEO F411RE development board, a 9-axis accelerometer, an ESP8266 Wi-Fi chip and a 9V battery - Arm provided a hundred of these kits during the IoT workshop earlier that week - the group quickly assembled a circuit held together by jumper wires, electrical tape and hope.

Sensor assembly in progress. Placing the accelerometer in a consistent way is important when building multiple sensors.

Storing data

After the assembly, the team faced another challenge: where to store the data? Typically, one sends the data for small IoT sensor nodes to the cloud using LwM2M over CoAP or MQTT, but these protocols are made for streaming small amounts of data periodically (such as sending a temperature value every minute). When dealing with an accelerometer, you want data to be sampled many times per second and to stream this data as fast as possible. In addition, internet connectivity is not a given in Tanzania. So the engineers did not want to rely on a stable internet connection.

Cow with the sensor attached

One way would be to cache the data locally in flash or on an SD card, but the downside is that you need to physically retrieve the device afterward to read the data, which is not practical in a real life scenario. Thus, the team decided to do it differently. By setting up a local UDP server on a laptop on the same network as the cow, the sensor can broadcast its data locally, and the laptop can cache the data. Because UDP has almost zero overhead, you don’t waste any CPU cycles on network connectivity. This way, you can grab data 30 times per second, send it to the computer and upload it to the cloud (in this case, an InfluxDB time series database) when there is internet.

Gathering data and sending it over UDP (TCP would work, as well) with mbed OS 5 is easy:

// Structure to store the accelerometer readings

typedef struct {

char mac[17]; // MAC address to identify from which sensor the packets came

int16_t x[330];

int16_t y[330];

int16_t z[330];

} AccelerometerData_t;

// accelerometer readings are done on a separate RTOS thread

void accelerometer_thread_main() {

while (1) {

printf("Start reading data\r\n");

AccelerometerData_t accel_data;

memcpy(accel_data.mac, mac_address.c_str(), 17);

int readings[3] = { 0, 0, 0 };

int seconds = 10; // seconds

int timeout = 33; // ms. timeout between measuring

int intervals = seconds * timeout; // number of intervals (needs to match the AccelerometerData_t type)

for (size_t ix = 0; ix < intervals; ix++) {

accelerometer.getOutput(readings);

accel_data.x[ix] = readings[0];

accel_data.y[ix] = readings[1];

accel_data.z[ix] = readings[2];

wait_ms(timeout);

}

printf("X: ");

for (size_t ix = 0; ix < intervals; ix++) {

printf("%d ", accel_data.x[ix]);

}

printf("\n");

printf("Done reading data\r\n");

printf("Sending data\r\n");

socket.sendto("192.168.8.101", 1884, &accel_data, sizeof(AccelerometerData_t));

printf("Done sending data\r\n");

}

}

To retrieve the data, the group wrote a simple Node.js script that sets up a UDP server and listens for incoming packets. To decode the data structure, the team used the struct package, which makes it easy to pack and unpack C-style data structures from JavaScript.

const udpServer = dgram.createSocket('udp4');

const Struct = require('struct');

udpServer.on('listening', () => {

var address = udpServer.address();

console.log('UDP Server is up and running at port', address.port);

});

let messages = {};

udpServer.on('message', (message, remote) => {

let key = remote.address + ':' + remote.port;

// messages come in two with the ESP8266 chip that was used... wait for the second one

if (!(key in messages)) {

setTimeout(() => {

let totalLength = messages[key].reduce((curr, m) => curr + m.length, 0);

if (totalLength === 1470 + 528) {

// now my message is complete

let pos = 0;

let buffer = Buffer.concat(messages[key]);

let entry = Struct()

.chars('mac', 17)

.array('x', 330, 'word16Sbe')

.array('y', 330, 'word16Sbe')

.array('z', 330, 'word16Sbe');

entry._setBuff(buffer);

entry.fields.x.length = entry.fields.y.length = entry.fields.z.length = 330;

console.log('Got accelerometer data for', entry.fields.mac);

// now send the data to a cloud of your choice… read the data via `Array.from(entry.fields.x)`

}

else {

console.log('msg was incomplete after 200 ms...', totalLength);

}

delete messages[key];

}, 200);

}

messages[key] = messages[key] || [];

messages[key].push(message);

console.log('UDP Receive', remote.address, remote.port, message.length);

});

udpServer.bind(1884, '0.0.0.0');

Analyzing data

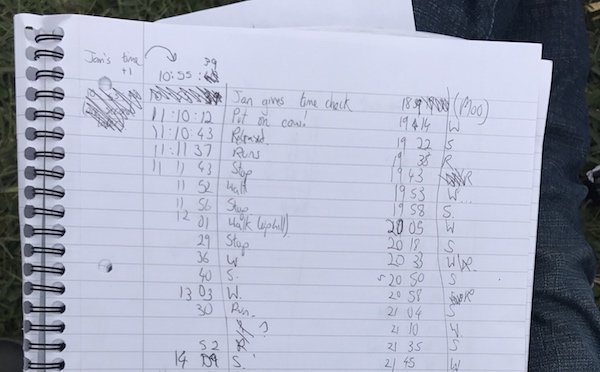

With everything in place, the engineers attached the sensor to the cow, and let it run wild. At the same time, they manually tagged what the cow was doing at which point in time, so they could tag the data later and use the tagged data for a machine learning algorithm.

With the data in the cloud, they could cross-reference it with the manual activity tagging and see if they could draw any conclusions from it. The first trait they looked at was standing still or running, as it should show up quite clearly even when analyzing the data manually. Damon Civin quickly started a Jupyter Notebook and visualized the data live in the field. At the same time, students digitized the tagged data, so they would have a coherent set of tagged training data that could be used in a machine learning model.

Analyzing data live in the field

Conclusion

Going into the field to gather data is exciting because it goes beyond the theory behind the Internet of Things. Grabbing data from a sensor becomes a lot more exciting when the sensor is attached to a cow. The team also saw some interesting issues with our current approach, such as the cow running out of range of the Wi-Fi hotspot. The sight of 10 people running after a cow with a laptop and a hotspot must have been hilarious.

It’s going to be interesting to see what people will do with the dataset. So far, the group has gathered around an hour of data, but local initiatives have started in Kenya to replicate the research on a wider scale. It would be great if farmer’s lives became easier thanks to the technology created during this conference. If you want to play with the data yourself, you can grab it here. The software the students used during the fieldwork is here (server) and here (firmware).

This was only one of the activities that Arm did in Arusha. We also visited a chicken farm, where we tried to analyze why chicks crowd at the same place in a hen house, ran a workshop during the summer school with 60 participants and worked with local academics and entrepreneurs to solve their data science needs. You can read more about that in a follow-up blog post by Damon.

-

Jan Jongboom is Developer Evangelist IoT at ARM. Damon Civin is Lead Data Scientist for ARM. Both have not grown up at farms.